Quadruped Crowd Navigation

ProjectFor my capstone project for my MS in Robotics degree at Northwestern University, I implemented the Bayes Rule Nash Equilibrium (BRNE) algorithm onto a Unitree Go1 robot using ROS 2. This allowed the robot to efficiently navigate through large crowds of people without collisions.

BRNE Algorithm

The BRNE algorithm was developed by Muchen Sun, my mentor for this project. The core idea of this algorithm is to model the strategy of each agent in the distribution space rather than a discrete path. A simple Bayesian update scheme to the distributions of each agent is guaranteed to converge to a global Nash equilibrium – where each agent has an optimal path, and no strategy that any of the agents can take can improve their own trajectory.

The BRNE algorithm produces trajectories that minimize a cost function of the following form:

\[a_3 \cdot \left(2 - \frac{2}{1 + \exp\left(-a_1 \cdot d^{a_2}\right)} \right)\]Where \(d\) is the distance between two agents, and \(a_1\), \(a_2\), and \(a_3\) are parameters that adjust how close the agents are willing to come to each other during their trajectory. This function can be thought of as the “risk” of this trajectory point.

Visualization of the cost function for the BRNE algorithm.

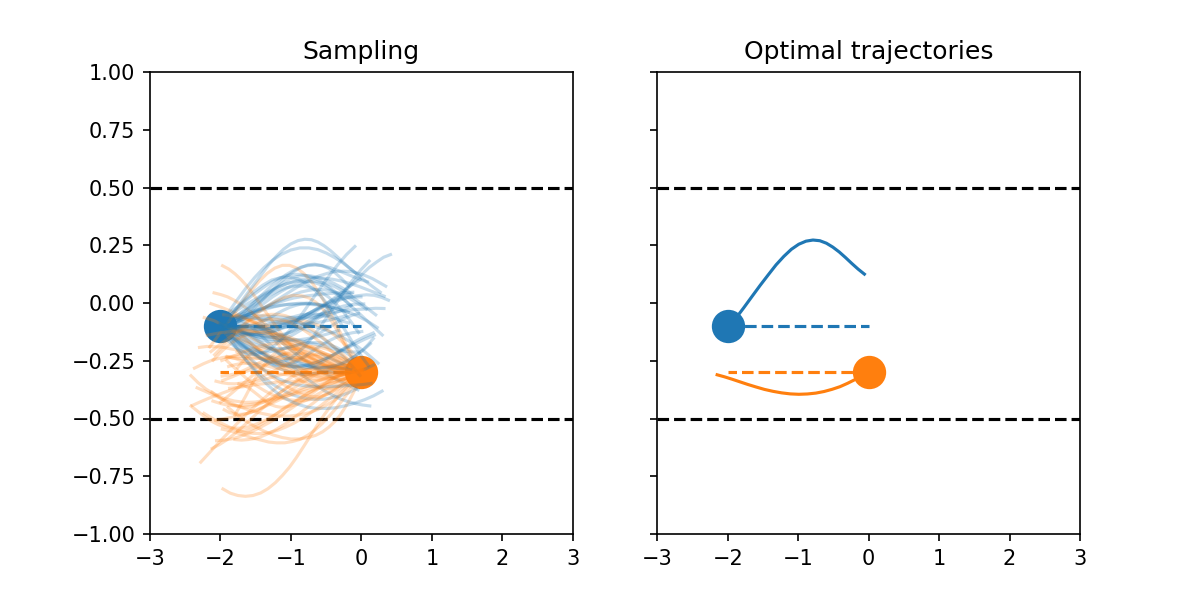

The first step in this algorithm is to generate trajectory samples for all agents. After this, the maximum cost for all trajectory samples between all pairs of agents is computed, which quantifies how “risky” each of these trajectories are. Finally, there is an iterative Bayesian update process which assigns a weight to every agents’ possible trajectories. The optimal trajectory for each agent is the weighted sum of these samples. A simple example with two agents is outlined below.

In this example, two agents are in a hallway. The blue agent wants to walk to the right and the orange agent wants to walk to the left, and their nominal desired paths if no other agents were present are described by the dotted line. The left panel shows the randomly generated trajectory samples for each agent, and the right panel shows the optimal trajectories after 10 Bayesian updates. This also includes a final collision check to ensure that the samples that go out of the hallway's bounds are not considered.

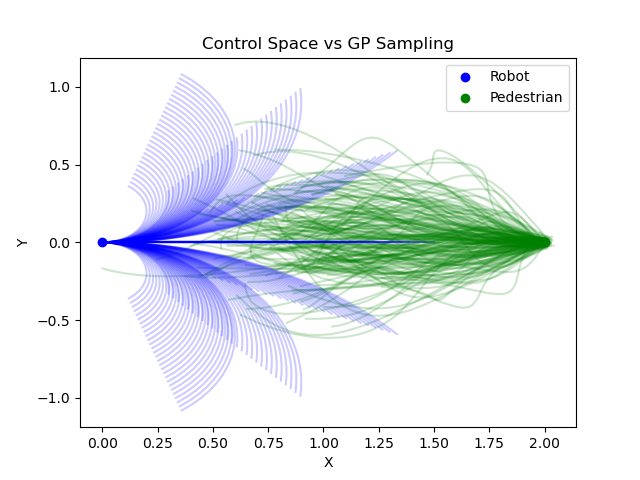

There are a few add-ons for controlling a robot in practice. Every iteration, the algorithm should receive the most up to date pedestrian data as well as robot location. It uses this to generate a set number of trajectory samples for each pedestrian using a Gaussian process parameterized by the agent’s intent and flexibility – which are also tunable parameters. The robot is modeled as a differential drive system and its samples are generated in the control space of linear and angular velocity. After the BRNE optimization, the controls that lead to the optimal robot path are published. BRNE’s updates to the trajectory plan should occur at a goal rate of 10 Hz.

Comparing trajectories of the robot and a pedestrian which are heading towards each other. 196 samples were generated, each simulating 25 timesteps of the trajectory.

C++ and ROS 2 Development

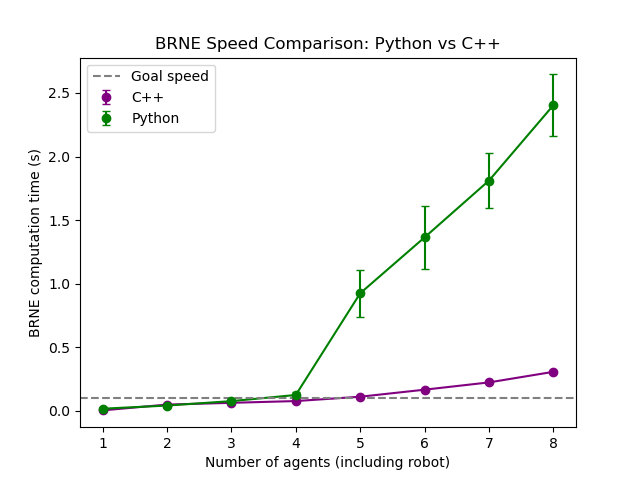

My contribution to this algorithm has involved converting existing code from Python to C++ and optimizing some matrix calculations. The Python version of this algorithm uses Numba for optimization. This has successfully worked in field tests, but requires around 20 seconds every time running to compile. Additionally, through stress tests, I found that the runtime blows up when the algorithm considers more than 4 agents (including the robot) – see below.

My C++ BRNE Library uses Armadillo for matrix operations and OpenMP for parallelization. I was also able to reduce the number of loops in a few core functions by using Armadillo to apply the same operation to all elements of a matrix, as well as exploing the symmetry of the cost function between each pair of agents to reduce the number of matrix operations needed during its calculation. The resulting speed is marginally faster than Python for small numbers of pedestrians, does not blow up at 5 agents, and even scales more efficiently if more agents need to be considered in the future. I also created some unit tests in order to confirm the numeric accuracy of the algorithm if more optimizations are added.

These times were generated running the appropriate BRNE ROS node in simulation using 196 samples per agent and 25 timesteps per sampled trajectory. The scatterplot points are the average computation time and the errorbars are the standard deviation over 100 timer iterations.

In addition, I created a ROS 2 C++ package to wrap around this library. When given pedestrian data and robot odometry information, it will use BRNE optimization to publish the optimal trajectory at 10 Hz. Before I started to incorporate real pedestrian and odometry data, I created a simulation to test the runtime and performance of the algorithm with both static and moving pedestrian locations – shown below.

System Design

As the BRNE trajectory updates should be published at 10 Hz, the perception data (robot odometry and pedestrian positions/velocities) needs to be published faster than this baseline. The biggest challenge with this project was figuring out the best way to obtain the necessary perception information at the necessary update rate.

Base Level System Design. I am using the control node in the unitree_nav package to process the commanded robot velocity from the trajectory plan into high level Unitree SDK commands.

As a baseline, I needed to run ROS 2 nodes both on my computer and on the onboard Jetson devices inside the robot. Alongside Matthew Elwin, I set up the Wifi hotspot on the Unitree’s Raspberry Pi to behave as a bridge between WiFi and Ethernet. This allowed me to run ROS 2 nodes on any device in this network and made the system truly wireless.

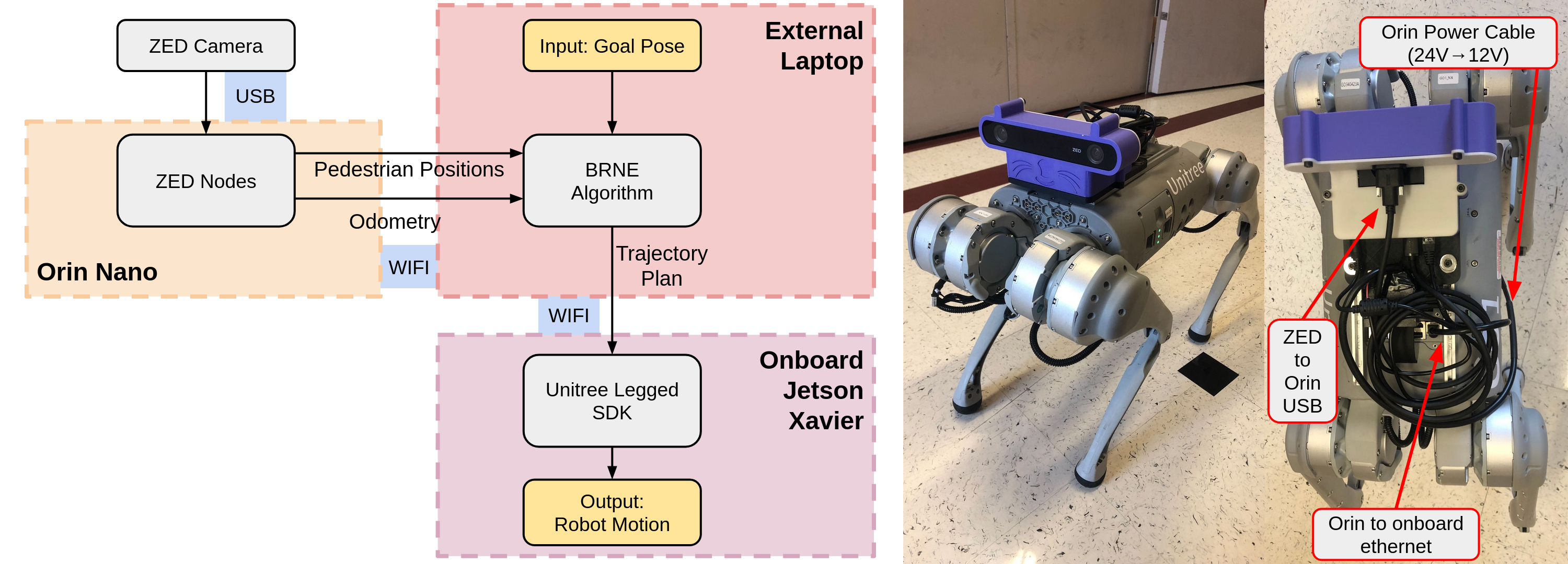

Final System Design: Orin Nano + ZED 2i

The current system uses a Jetson Orin Nano board and ZED 2i camera mounted onto the robot to handle the perception updates. The ZED camera provides robust visual odometry and has built in ML models that are capable of 3D object tracking – including pedestrian tracking. The Orin Nano has CUDA and a strong enough GPU to handle the requirements of the ZED SDK. As NVIDIA only supports up to Ubuntu 20.04 for the Orin Nano, and all of my other devices in my network are running 22.04 and ROS 2 Humble, I am using Isaac ROS (a 20.04, GPU-powered version of Humble) to ensure that all topics can still be seen throughout the network. Additionally, I created a custom power cable with a DC-DC converter to power the Orin Nano at the appropriate voltage from the battery inside of the Go1 (thanks to Davin Landry for the help!).

The core BRNE algorithm executes on my external computer as the Orin Nano does not have good enough CPU for the trajectory optimization calculations. In the future, it might be possible to use CUDA to optimize the performance of the algorithm to this device, and once again have everything onboard.

System design with an onboard Orin Nano (thanks to David Dorf for designing and printing the Orin/ZED mount!)

I went through two previous system designs before settling on this one. Check out some more details on what these systems looked like and why I didn’t continue with them below.

Previous System Designs

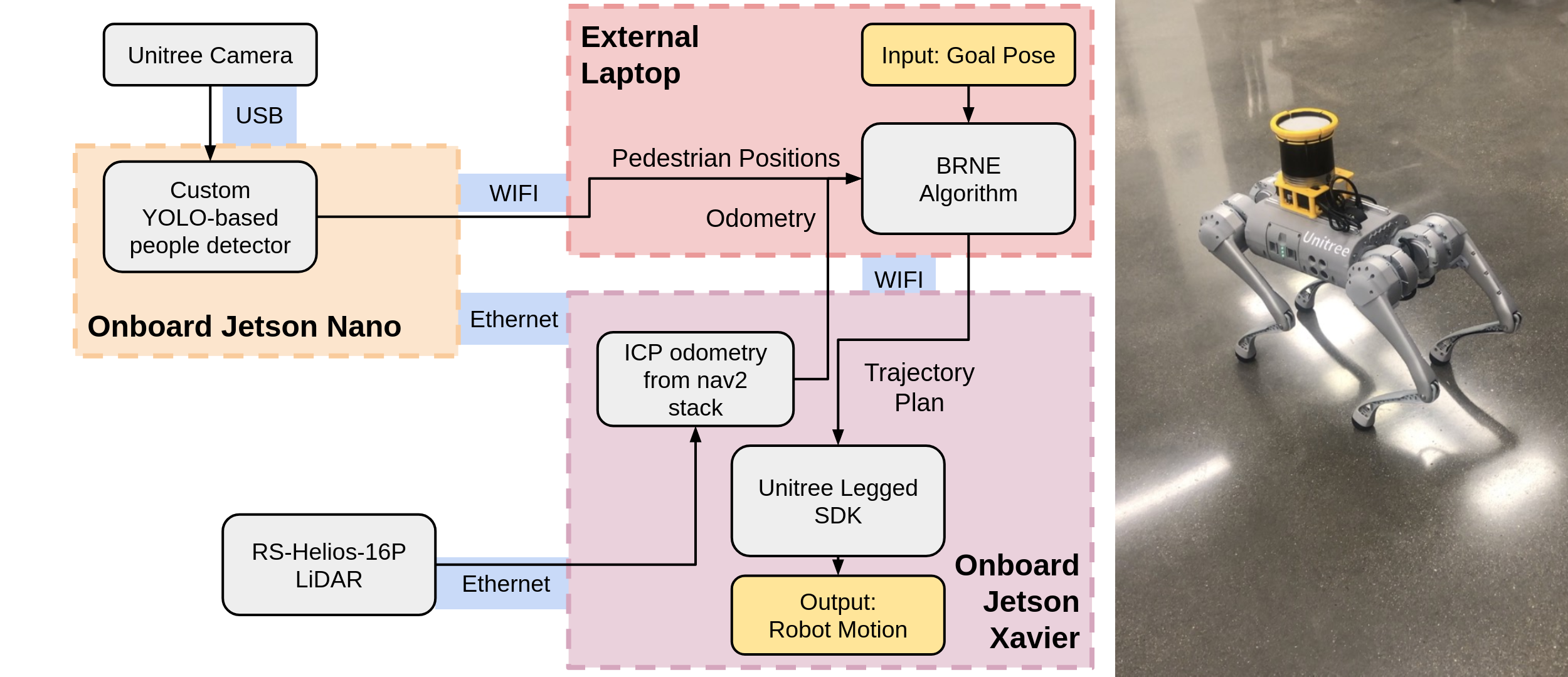

Iteration 1: All Unitree Hardware

The first plan for the system design was to use the built in USB cameras to the Unitree as well as the RS-Helios-16P LiDAR module it came with to provide the perception data. The Unitree Go1 internally has two Jetson Nano boards (one in the head and one in the body) and one Jetson Xavier board (in the body). The Jetson Nano boards are connected to USB cameras that are in the head and the right and left of the body. The idea was to have the Jetson Nano boards running YOLO-based people detection models which would feed into the BRNE algorithm. If this could be running on both Jetson Nano boards, you could track people from the front as well as the side of the robot, which is a big advantage over using a single camera. The odometry would come from using the unitree_nav package on the onbard Jetson Xavier which uses ICP odometry.

Proposed system design with onboard LiDAR and onboard Unitree USB cameras.

There were a number of problems with this system. First, interacting with the Unitree cameras was very difficult. The cameras are unreadable by default, unlocked when you use the closed-source Unitree Camera SDK, and locked again when you stop using it. The Unitree camera SDK is also buggy and and has dependencies on very old versions of OpenCV, which makes it difficult to compile on a 22.04 system for use with ROS 2. For around three weeks, I tried to find a workaround that would allow me to read from their cameras using standard Linux tools -- check out this post for more information on my reverse engineering progress -- but ultimately found it too much of a time sink.

The main reason this system was not feasible was because the onboard Jetson boards on the Unitree were too slow. After setting up the LiDAR and running the nav2 stack on the Jetson Xavier, I only received odometry updates at 5 Hz. Mapping and localizing at the same time was not possible as if the robot moved too quickly, the map would not generate correctly, so I used pre-built maps of my testing environment made by manually teleoperating the robot very slowly. The need to have a map ahead of time also severely limited the deployability of this robot. Ultimately, I did not even attempt to deploy a people detection model on the Jetson Nanos, since if the more powerful Jetson Xavier could not compute relatively simple odometry updates quickly enough, there was no chance that a more complicated ML model on the Jetson Nano would be able to keep up with the speed requirements.

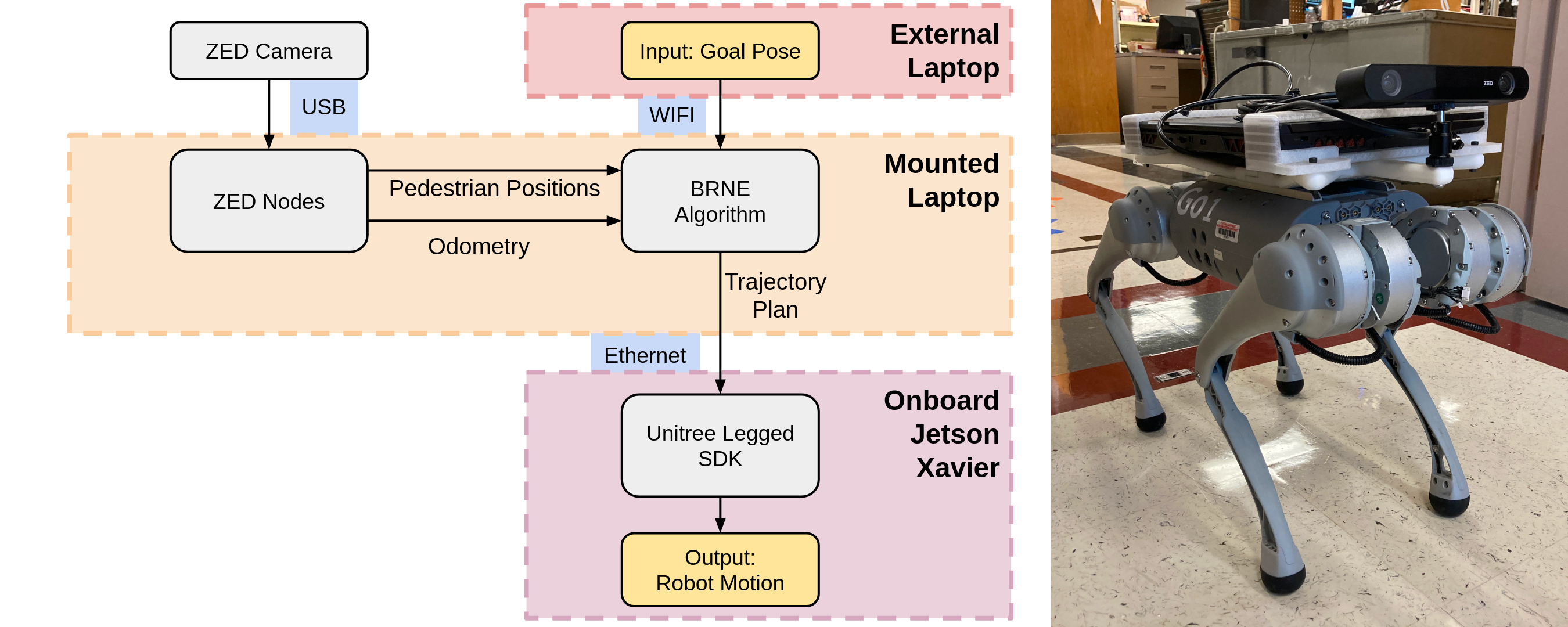

Iteration 2: Laptop Mount + ZED 2i

As pedestrian tracking and odometry updates from the onboard Unitree devices was not feasible, we moved to using a ZED 2i camera. The constraint of using the ZED is that it requires CUDA and a powerful GPU, which none of the onboard Jetson boards were able to provide. For this purpose, we mounted a System76 Adder WS laptop to the back of the Unitree so that it could process the perception information. Since the BRNE algorithm is CPU intensive while ZED processing is GPU intensive, it is possible to run essentially the entire system on this mounted laptop.

System design with an onboard laptop (thanks to Davin Landry and David Dorf for designing and printing the laptop mount!)

While this performs all of the relevant computation onboard, there are some downsides to this approach. First, it was difficult to design a mount that securely held the laptop on the back of the robot. The robot had trouble with agile movements and was more prone to falling over from imbalance. With all of the extra weight, the motors also overheated faster, and devices onboard the robot tended to fail sooner (namely the Raspberry Pi provided WIFI hotspot).

Additional Visual Processing

The BRNE algorithm needs the position and velocity of nearby pedestrians. While the ZED camera is very robust at tracking pedestrian position, its velocity estimate is not very consistent. We found it was a better estimate to do a simple frame-to-frame velocity calculation by comparing the location of each pedestrian in subsequent frames and dividing by the time difference between the updates. This is also run on the Orin Nano and results are shown below. While this approach is still not perfect, it is significantly smoother than using the raw message data.

Result of pedestrian position tracking from the ZED camera and my custom frame-to-frame velocity estimation.

I created a custom Pedestrian message type that was more concise than the ZED topic, containing only position, velocity, ID, and timestamp. As the pedestrians are detected relative to the ZED frame, I broadcasted their location using tf in order to convert them into the world frame. I also created an additional tf frame to connect the location of the ZED camera frame (and the origin of the ZED’s odometry) to be statically offset from the center of the robot, creating a new odometry topic with the same offset. This allows me to generate the optimal controls with respect to the location of the center of the robot.

Results

I’ve created a stable platform that is available to run more experiments on social navigation in the future. We’ve verified that this robot can successfully operate in crowded spaces and has a high level of reactiveness to pedestrians. Having the ability to test features of this algorithm on a physical robot with real people will help improve the functionality of BRNE in the future. Additionally, my simulation framework is an easy way to test tuning parameters and characterizing the runtime. Below is a compilation of many of my final tests, where we tried to put the system under as much stress as possible to understand its limitations.

Future Work

There are a lot of ways that the system I’ve made could be added to or improved on, and I am really excited to see how it evolves in the future! Below I’ve listed a few of my ideas for new work.

- Run the BRNE algorithm onboard the Orin Nano, or another mounted device such as the more powerful Orin AGX.

- Adjust the robot’s sampling. Currently, the robot is modeled as a simple differential drive system and the samples are generated over a space of linear velocity and angular velocity. However, the Unitree robot is omnidirectional, and the controls can consist of \(v_x\), \(v_y\), and \(v_\theta\). It also may be beneficial to consider controls that can vary over the planning horizon as opposed to only considering constant linear and angular velocity.

- The pedestrian velocity estimation could be smoothed out by using a filter, although it’s unclear how much of an effect this would have on the resulting trajectories.

- Visual odometry from the ZED was pretty robust, but drifts when people are very close to the camera. If this system is to be used in even denser crowds, a better odometry solution is needed.

- One of the biggest problems the robot had during testing was walking outside the predefined bounds of the space. As a related point, the BRNE algorithm currently has no way of recognizing non-pedestrian obstacles. Considering static obstacles as “agents” with zero velocity would make this a general purpose planner, although this would require a huge re-work to both the algorithm and the visual processing.

References

- Muchen Sun, Francesca Baldini, Peter Trautman, and Todd Murphey. ”Move Beyond Trajectories: Distribution Space Coupling for Crowd Navigation.” In Robotics: Science and Systems (RSS). Virtual, 2021.

- Muchen Sun, Francesca Baldini, Peter Trautman, and Todd Murphey. ”Mixed-Strategy Nash Equilibrium for Crowd Navigation.” Under Review. 2023.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to everyone who helped me through this project!